Emily Gartner

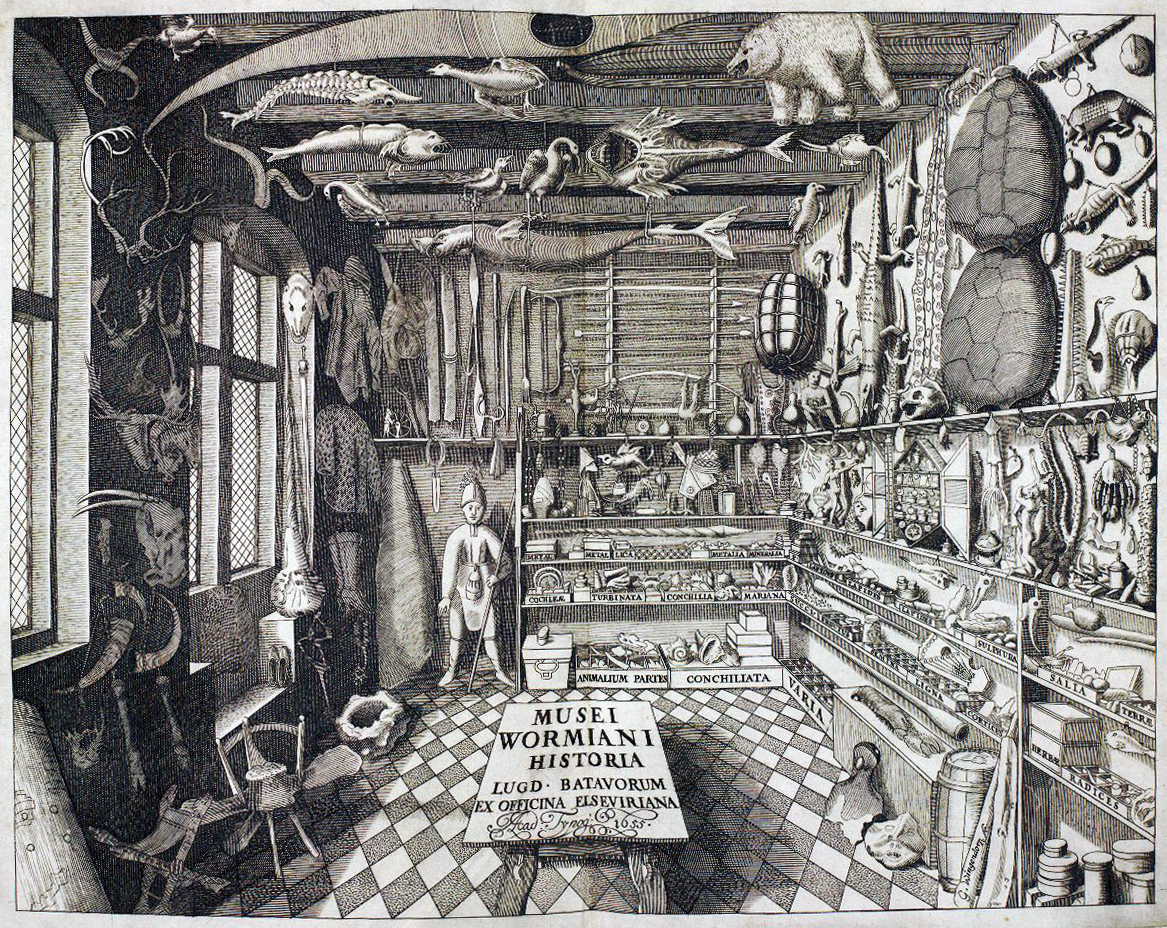

In the earliest days of the museum, starting in the 16th and 17th centuries, there were no grand, national galleries, interactive public exhibits, or (sadly) heritage homes to visit. Back then, the museum was nothing more than a box in the homes of the influential. A cabinet filled with things that were exotic and exemplary of the owner’s power and prestige. People would show off these wunderkammers, or cabinets of wonders, to their guest, and have cabinet makers create and paint cupboards, drawers, even whole theatres for their growing collections. These cabinets grew in popularity and reached the point where the rich and noble were not alone; middle class merchants were expected to also keep and curate their own, more modest, cabinets. All were unique and, while they do follow the modern museum idea of preserving and displaying things for visitors to look at, they are very different from our museums today.

"Musei Wormiani Historia", the frontispiece from the Museum Wormianum depicting Ole Worm's cabinet of curiosities.

When we think of a museum or exhibit, generally there is some sort of subject theme to them, which their exhibits reflect. For example, Dalnavert is a Victorian heritage home. Its theme is history, specifically Victorian Canadian history. The curator is not likely to decide to suddenly display a lion skull or a Roman dagger because, as cool as they both are, they don’t really fit with the museum’s mandate. Cabinets of curiosities, however, were different. They were meant to include all sorts of different objects which might have nothing in common except they were all cool, rare, or expensive. This wasn’t just to show off the owners wealth (although they did that too), but was to create a sort of image of the world through the eyes of the person curating the cabinet. To make a good cabinet, one truly representative of the whole world, the owner had to include objects that were from the natural world, relics from the ancient world, art, exotic artefacts, and even mystical or magical things. The arrangement of the collection was entirely up to the owner. So they might include objects representative of the natural world, including plants, animals, and minerals alongside art or artefacts from different parts of history or the world. A lot of them were arranged based on symmetry of colour or size. Or they could arrange them to tell a story, either of the family or person who owned it, or maybe of the universe as they knew it.

Pitt rivers Museum, Oxford

Photographer: Danny Chapman, Flickr

Cabinets fell out of fashion with the introduction of the modern public museum. By the Victorian period, while families might have collections, cabinets were of less interest. Today, cabinets of curiosities exist more as a novelty than as a social status indicator or as a modern museum. Some do still exist as museums, like the Pitt Rivers museum in Oxford, which continues to display its artefacts cabinet-style, with lots on display, but with little labelling or clear theme. Part of the appeal of the place is that it exists as an example, a snapshot, of what a museum based on a cabinet would have looked like. Other museums, like the British or Ashmolean Museums have cabinet of curiosity roots, with their collections initiated by a personal cabinet, but have since evolved into more modern institutions. This was often done to make their institutions more accessible or better suited to house their collections, but in the process they did away with how their collections might have been laid out when they were first obtained.

Some people have also made their own modern versions of the cabinets. They are a bit different now, though, as they have become associated with the weird or creepy, and are now often used for shock effect. For instance, in London there is the Viktor Wynd Museum of Curiosities, which is full of artefacts many of which you can buy, including several skulls, taxidermy, and dolls, all of which vary from the bizarre to the grotesque. This type of museum is not as much a historic example of a cabinet of curiosities as much as a modern interpretation of the style. Cabinets during the Renaissance would not have been seen as creepy, but as quite fashionable (despite the skulls). Still, the idea of a space full to bursting with items of wonder is very true to the original cabinet trend’s hallmarks.

Viktor Wynd in front of his museum.

Photographer: Oskar Proctor

Over the centuries, our perception of what is and is not a museum has changed. Cabinets of curiosities have gone form the only game in town to being representative of the fancies and fantasies of our ancestors. Yet we still, as people, continue to collect and display things in our homes, some natural and others man-made. So take a look around your house and see: could you build a cabinet of your own personal wonders?