Raminder Saini

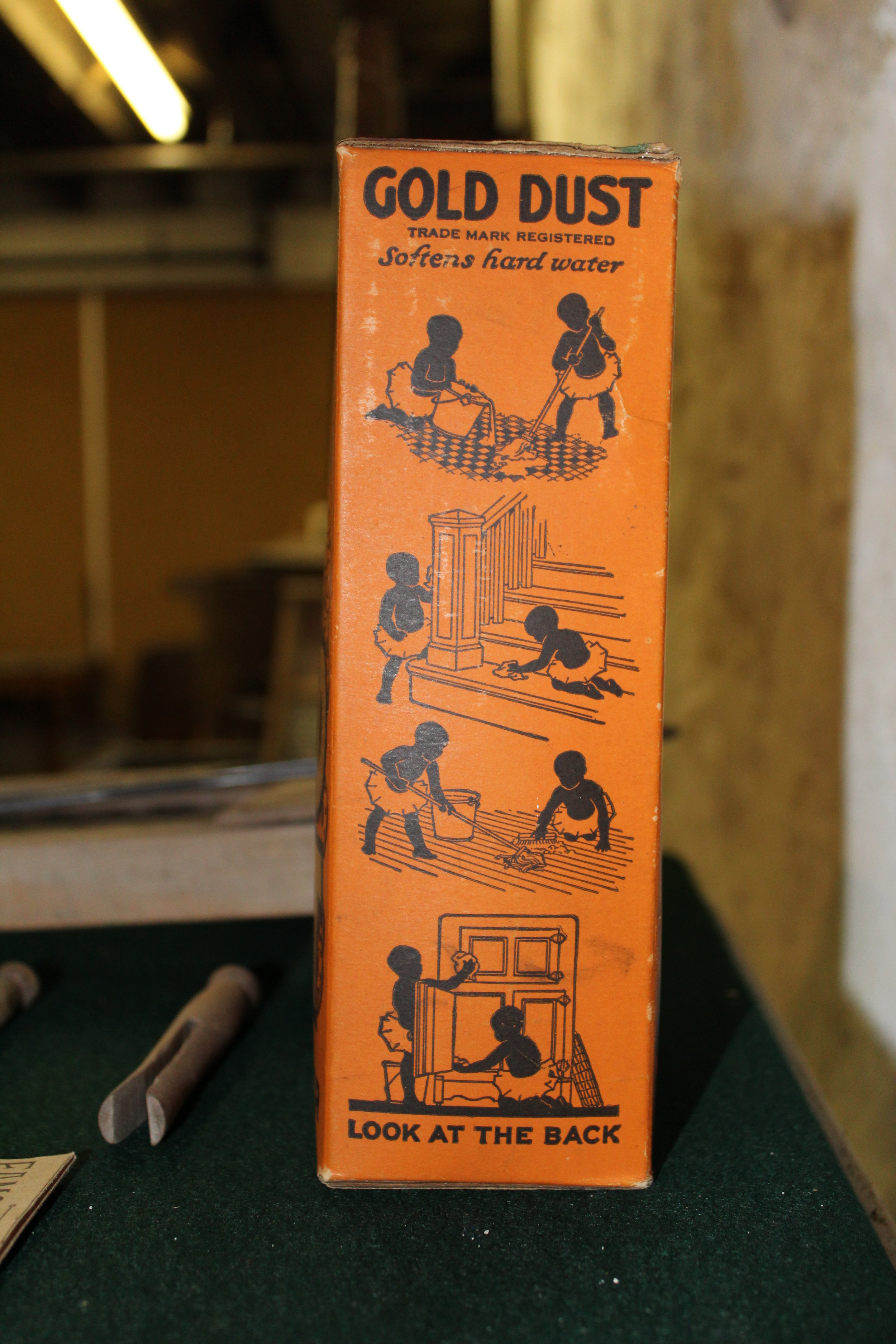

“The Fairbank ‘Darky Twins’ on the ‘Gold Dust’ package are as familiar to the average housewife as the face of the family clock.” - Maine Farmer, April 1, 1897

The “Gold Dust Twins” were a pair of African American caricatures displayed on a popular box of washing powder from the 1880s to the early 1900s. These twins, grotesquely referred to as “the Darky Twins” by the Maine Farmer in 1897, symbolized racial attitudes that Victorians often held at the time. But who were the twins? And why should we be talking about washing powder?

Soap in the late 1800s represented more than the physical aspect of “getting clean.” The Victorian idea of cleanliness became tied to the concept of imperialism and Victorian superiority. Many Victorians, as it is well known, felt superior to the people they colonized (from Africans and Indians to Indigenous communities in Canada). Victorians also came to associate whiteness with cleanliness and blackness with dirtiness – a notion co-opted rather successfully by soap manufacturers in racialized advertisements. Take for example an advertisement for Pears’ Soap:

Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Pears-1884.jpg

This ad plays on the themes of imperialism and racial stereotypes that were common to the Victorian era. In the image to the left you have an African child being placed into a tub and about to be washed with Pears’ Soap, which is held in the hand of the white child. In the next image, the African child no longer has black skin. The child has been scrubbed clean of its “dirtiness” and has thus been “civilized” (or so it is implied). As the ad reads, “I have found PEARS’ SOAP matchless for the Hands and Complexion.” This rather horrific advertisement plays on the Victorian mission to “civilize” colonized peoples.

At Dalnavert, the laundry soap on display is “Gold Dust Washing Powder.” “Gold Dust” was an American soap, manufactured by the N.K. Fairbank Company in Chicago. This company had factories in both North America and Europe. According to The New York Times (March 17, 1895), this soap was the leading washing powder at the time. It is only fitting then that a box of it lies in the laundry room at Dalnavert.

More of an all-purpose cleaner than strictly laundry soap, “Gold Dust” was meant to make the life of a housewife easier. How? Well, the sides of the box depict two African American twins who appear to happily be doing household chores. The twins, incidentally, represent the power or strength of two cleaners in one, efficient washing powder. For middle-class Victorians, the less work a housewife could do with her hands, the more time she could devote to leisure activities that would better allow her to mimic the lifestyle of the upper classes. As it stood, one main division between middle and upper class families was that the upper classes never had to sully their hands with simple household chores—that’s what servants were for!

This image, though, of African American twins happily doing housework is yet another expression of contemporary racial attitudes. Since the washing powder is American, it is a different kind of advertising from that of the Pears’ Soap Company. Arguably, the image of the “Gold Dust” twins align better with slavery in America and the use of Africans for domestic labor than simply Victorian ideas of cleanliness and civilization. But regardless of the difference, racial soap advertisements enforced widespread ideas of late-nineteenth century imperial and racial superiority. Worse, people literally bought into these stereotypes by buying products from N.K. Fairbanks and Pears. Accordingly, the soap on display at Dalnavert goes beyond merely displaying a common household item and instead showcases a connection to the larger forces at play in both North America and the British Empire when it came to cleanliness.