The Many Forms of the Victorian Novel

Ruth O.

From Charles Dickens’ Great Expectations to George Eliot’s Middlemarch, countless celebrated novels of the 19th century can still be found in bookstores today. If you were to crack open a modern edition of a Victorian novel, however, your literary experience would be incredibly different from that of 19th century readers. So how were readers consuming these stories when they were first published? And what makes them different from the novels sitting on our bookshelves today?

The first chapter of Great Expectations published in All the Year Round, 1859. Source: archive.org/details/allyearround01dick/page/n4

Serialization

Serialization meant that a novel was published in weekly or monthly instalments. Instead of buying a completed book, readers would purchase chapters or parts as they were released. (Think of it as watching a new TV series as it airs rather than binging an entire show on Netflix). Instalments of serialized novels were often published in periodicals or literary magazines.

This format meant that texts were easy to carry around, easy to share with others, and more affordable – readers did not have to pay for a whole novel upfront, but could put a portion of their income each week or month towards these publications. Cornhill Magazine, for example, ran monthly editions for 1 shilling (12 pence), and the Dickens-owned All the Year Round ran weekly editions for only 2 pence. While serialized novels were largely marketed towards and consumed by middle-class readers, the twopenny weeklies of All the Year Round were also accessible to members of the working class[1].

Serialized fiction was also known for popularizing the cliffhanger at the end of its chapters. Just as a cliffhanger makes you crave the next episode of your favourite TV show, it also incited Victorian readers to purchase future instalments of the novel they were currently reading. During the wait between instalments, readers would frequently write to one another with reactions to recent chapters; occasionally, they would even write to the authors themselves with their emotional responses. This reader-response phenomenon would sometimes prompt authors to change plotlines and introduce new characters based on the opinions of their readers.

Examples of serialized novels: Middlemarch, The Pickwick Papers, Great Expectations, The Woman in White, Far from the Madding Crowd

In this 1869 illustration from London Society, readers clutch their books outside Mudie’s Select Library in London. Wikimedia Commons.

The Three-Volume Novel

Many Victorian novels were published in three volumes, either as a first run or after serialization. These texts, known as “triple-deckers”, sold for 31 shillings, 6 pence. For reference, this price was more than the weekly industrial wage and was a deterrent even for middle-class readers. As a result, triple-deckers were bought by circulating libraries to be borrowed by middle-class readers one volume at a time. Through a circulating library, consumers paid about 21 shillings (1 guinea) a year in subscription fees and in doing so, were able to borrow one volume of a novel at a time. This option was much cheaper than purchasing one or more triple-deckers.

Mudie’s Circulating Library, based in London, and W. H. Smith’s Subscription Library, established across British railways, dominated this industry in the Victorian period. While the three-volume novel eventually declined in popularity towards the end of the 19th century and was replaced by texts of varying lengths, circulating libraries remained the principal means of borrowing books into the 20th century.

Examples of three-volume novels: Jane Eyre, The Mill on the Floss, The Tenant of Wildfell Hall

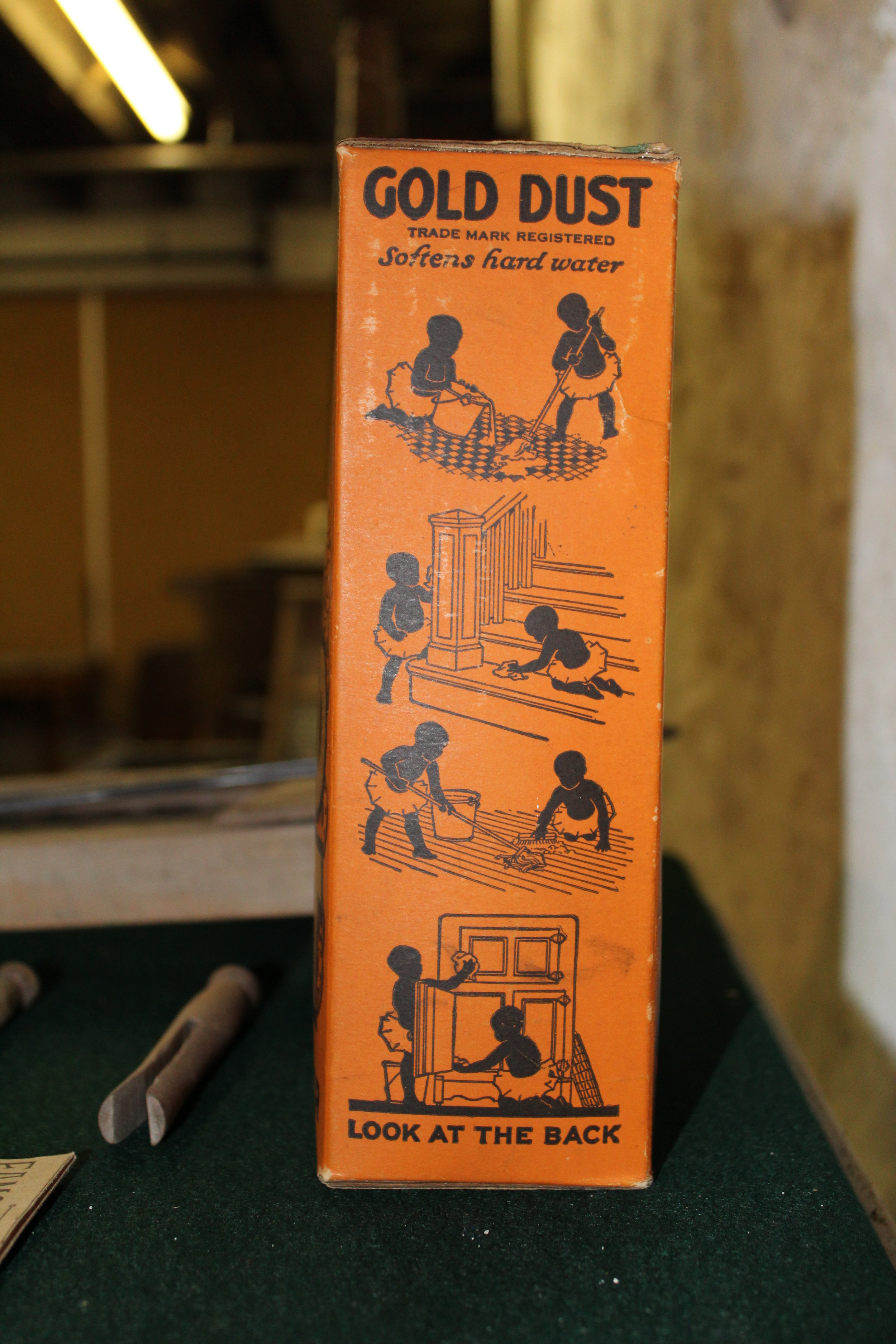

Yellowback cover of Lady Audley’s Secret by Mary Elizabeth Braddon. Source: archive.org/details/36163849.2555.emory.edu

Single-Volume Novels

After serialization or three-volume publication, novels were typically re-printed in single-volume format for about 3 ½ shillings. By the mid-19th century, these stand-alone texts became even cheaper through their publication as 1 shilling “yellowbacks” (named as such because they were bound between two boards covered in yellow paper). Yellowbacks made popular texts more accessible not only because they were more affordable for the working class, but also because they were distributed in railway bookstalls throughout the country. By the late 19th-century, yellowbacks were largely replaced by paperback novels, a format that is still purchased to this day.

The String of Pearls, the Penny Dreadful that first introduced the characters of Sweeney Todd and Mrs. Lovett. Source: www.bl.uk/romantics-and-victorians/articles/penny-dreadfuls#

Penny Dreadfuls

While the decreased price of yellowbacks allowed working-class readers to enjoy re-prints of popular novels, lower-class audiences were also the primary consumers of sensational adventure novels known as “Penny Dreadfuls”. As the name suggests, these stories were sold for only a penny and were published in instalments on cheap pulp paper. Tales would often unfold over months or even years and would feature monsters, detectives, kidnappers, highwaymen, and plenty of other gruesome and Gothic figures.

Penny Dreadfuls were particularly popular among working-class youth, and by the 1880s their avid consumption instigated a “moral panic” among middle-class Victorians. Many believed that the “scandalous” content of Penny Dreadfuls would lead lower-class youth into a life of degeneracy and they blamed the novels for inner-city violence and crime. In reality, this misguided middle-class concern was based less in truth and more in the fear of an independent working class that did not adhere to the upper classes’ moral expectations.

Examples of Penny Dreadfuls: Varney the Vampire: Or, the Feast of Blood; Sweeney Todd: The Demon Barber of Fleet Street

[1] Ehnes, Caley. Victorian Poetry and the Poetics of the Literary Periodical. Edinburgh Critical Studies in Victorian Culture. Edinburgh: EUP, 2019.